For years, we produced catalogs that sold the things we made and loved. In them, we told stories of the men and women across America doing good work.

Their stories inspired us and we began to ask why we didn’t do it more. GIANT Magazine is the result of those conversations. In issue two, we take the opportunity to highlight people in pursuit of their passions. From vintage vehicle restoration to craftsmanship and surfing, we invite you to read these stories of passion, community, and pursuit.

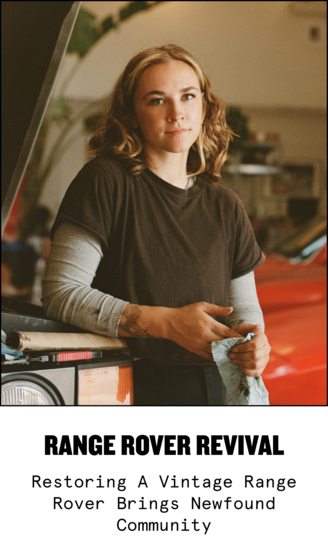

The silver 1990 Range Rover Classic grinds along the off-road terrain heading up the Santiago Mountains outside of Los Angeles, wheels churning against the dirt to leave a pillow of dust in its tracks. Twenty-five-year-old Elise Talley is in control in the driver’s seat. Skillfully, she steers her SUV up mountain switchbacks in time to see the sunset.

Owning a vintage, first-generation Land Rover was always Elise’s dream. The vehicle offers a snapshot into a specific era of automotive engineering. With its legendary boxy design and high-performance features like four-wheel drive and robust suspension systems, it blends luxury, capability, and nostalgia into one iconic package.

Elise got her Rover for $2,000 cash just after her 16th birthday—despite her parents hoping she’d buy something more practical. But the fact that it needed serious work was part of the draw. For nearly a decade, Elise has painstakingly restored every inch of the car. There isn’t a single system, feature or corner she hasn’t tinkered with or upgraded.

Through hours of intense and intimate work, Elise has formed a bond with her Rover. When she’s not fixing it up, she’s taking it out to explore California’s mountains, beaches and deserts. To most, a car is just a car, but for Elise, it’s her personal obsession, source of community, daily driver and adventure companion. She keeps it alive, and in turn, it takes her where she wants to go.

Broken gaskets, aging braking systems, busted transmissions. These are promises of genuine fun to be had. For as long as she can remember, she’s loved fixing old things. The satisfaction comes from figuring out a problem and solving it with her hands. As a kid, that meant dismantling and rebuilding rotary phones or typewriters she’d beg her mom to buy her from local antique shops. After high school, it meant working as a restoration mechanic on other people’s classic cars. Now, in her day job, she’s moved from cars to rockets as an engineer at SpaceX. On nights and weekends, it’s back to the Rover.

Whether she’s disassembling the engine to make repairs or completely re-doing her gas tank, she relies on advice from an extensive community: YouTube videos, online forums, real-life advice from fellow auto enthusiasts and work sessions with friends. Often, she’ll head to her friend’s shop to be around others fixing up Porsches, Ferraris or race cars.

The group of people who revive classic cars is strong and diverse. She connects with them daily on Instagram and goes to car meet-ups at least once a month. These events come together organically: one person posts a date and place, and the crowd forms. People who have never met, instantly connected and bonded over their shared love for breathing new life into old machines.

The projects never end, and that’s a good thing. Elise says she craves the burst of satisfaction and confidence that comes with a completed job. Currently, she’s in the process of re-doing the interior, including the leather seat upholstery, removing and cleaning the carpet, soundproofing and re-veneering the wood paneling.

Elise sees her Range Rover as a lifelong project. She has no plans to give it up. Instead, she will continue to care for it as needed: fixing, rebuilding and enjoying as she goes.

The moment the ocean surges to create a wave, surfers must make a split second decision—go. There’s a thrill in the act. And a deep connection that exists between humans, the ocean, and the object bringing the two together: a board.

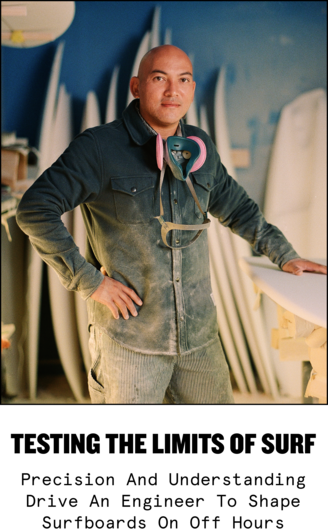

Zouhair Belkoura started surfing many years ago hoping to find that thrill. An engineer by training and a tech entrepreneur by trade, his mind is constantly tuned to perfecting whatever he’s working on. Surfing was meant to be an escape from this pursuit. To get him outside. To test him physically. But, true to his nature, he couldn’t leave his mind on the shore. Despite his efforts to just enjoy each wave for what it was, the calculations started: could he create the most optimal surfboard?

The process of making a surfboard hasn’t evolved much since the 1950s when Dale Velzy introduced the iconic “pig” model, revolutionizing wave riding by enabling turns instead of just straight cruising. Once dimensions are sketched out, crafting a surfboard boils down to three steps: shaping the foam, sculpting it and coating it with fiberglass and resin.

In 2019, Zouhair decided to test the limits of the “pig.” At first, he made two versions (a true engineer, he A/B tested). It didn’t take long for him to realize there’s no such thing as “optimal” when creating a wave-riding vessel. Optimal, after all, would sensibly be the most stable board. But a stable board won’t turn. What’s the thrill in that?

He had to think outside of the engineer’s mindset. The ideal board, he realized, varies from one rider to another: a shorter, lighter style for experienced surfers making tight turns. A longer board for beginners. Embracing this new perspective, he fell in love with the process of making. It wasn’t about crafting the best version. There was no 2.0 or 3.0 to strive for, just a board he could ride. And eventually, boards his friends could ride, too.

Like most custom surfboard makers, he starts by sitting down with each surfer to understand what they want the board to do and how they surf. Most often, they’re people he’s surfed with, so he tailors each board just for them, knowing how they like to maneuver in the water. He charges only for materials, not for his time.

Board shaping, like playing an instrument, is about feel—it’s personal, music coming from within. Zouhair first learned by watching other shapers on YouTube and observing locals with decades of experience. Yet he realized no one was doing it exactly the same, each craftsman had their own style. To develop his own, he relied on repetition and practice. A line of code is a line of code, but a line on a surfboard could be achieved by sanding slowly and steadily, or in one fell swoop, or some way in between.

Zouhair assumes surf purists may scoff at his work. But like any cover song, there is the original version and the new version. The new version is different, yes, but there’s the old stuff in there, too. The song remains the same in the dust-covered stall he shapes in at a local shop. And there’s harmony in every board.

In Japan, “shokunin” are masters of their craft. The direct translation into English “artisan” is not incorrect, but loses the spirit of what a shokunin does. A shokunin is hard to explicitly define, even among shokunin themselves. The path to this title is indirect — a lifetime, or even generational, pursuit of mastery.

In 1943, Joseph Eichler rented the Bazett House in Hillsborough, CA (designed by Frank Lloyd Wright). This inspired him to become a residential real estate developer with a focus on making Modernist single family homes accessible to a diverse range of buyers. Between 1949 and 1966, Eichler Homes built 11,000 houses throughout California — primarily focused in the Bay Area and Los Angeles. He hired architects to design model homes for each neighborhood, many of which have become the quintessential icons of California Modernism, and even more specifically the Second Bay Tradition. Second Bay Tradition homes are defined by post-and-beam design that emphasizes volume over ornamentation, and utilizes natural materials of the area, like old growth redwood and repurposed brick from the 1906 San Francisco Fire. Many Eichler communities still exist today, with new generations of homeowners who are dedicated to returning them to their former glory.

Zach and Jas bought their A. Quincy Jones & Frederick Emmons designed Eichler in the summer of 2021 after losing out on multiple other architecturally significant properties throughout the East Bay. They bought it from the second owner who had acquired the house out of foreclosure during the 2011 economic downturn. Sadly, many Eichlers follow this path: the original family ages out or can no longer take care of the house and it’s up to the next custodian to bring them back to life. Until recently, Eichlers weren’t worth any premium and many of them have been modified beyond repair by unknowledgeable owners and real estate flippers. The single carport atrium model (or CC-1854R for the enthusiasts) that Zach and Jas bought was rough, but the perfect starting point for their Eichler journey.

When most people think about fixing up an old house, the word “renovation” comes to mind. However, in this case “restoration” is the better language to use. Zach has been building and restoring bicycles, cars, and now houses for years — a self-taught pursuit in becoming a master of the minutia. Ever increasing attention to detail. Always taking that extra step that most consider as too costly, too time-consuming, or having too little return. Their most recent project involves replacing all of the thinline siding and demolishing the existing roof down to the original redwood tongue and groove boards — just so the new roof will be as low profile as possible while also aesthetically matching Jones & Emmons’ original design intent. Most homeowners would spray a new foam roof and call it a day, but that’s not the path of the shokunin.

Zach and Jas are taking their time. Slow is okay. Learning becomes a part of every day. Setbacks are very real, but documenting and continuing the tradition creates a path for others to follow and make their own. If you’re interested in the progress follow them @uchidelossantos, and if you’re looking for a Modernist home in the Bay Area to make your own, head over to @midcenturymachine.